Celeb Columns

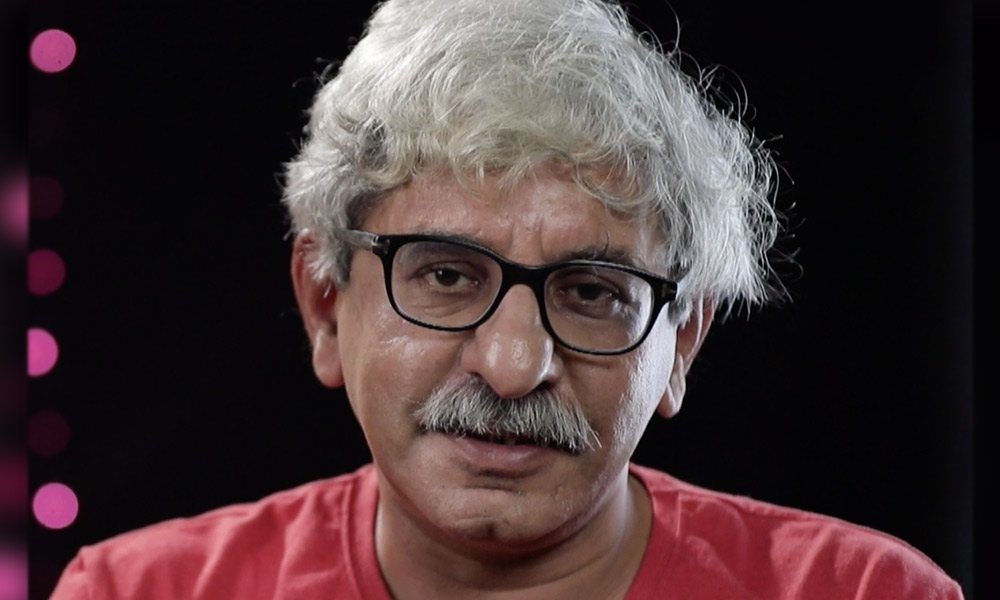

Sriram Raghavan speaks about Alfred Hitchcock’s cinematic brilliance and his influence on filmmakers – read exclusive column

In an exclusive column for CineBlitz, Sriram Raghavan talks about Alfred Hitchcock, his cinematic brilliance, his way of film-making and its influence on Indian as well as foreign movies!

Published

5 years agoon

My earliest introduction to Alfred Hitchcock was his droll visage on the covers of short story anthologies available on the streets of Kings Circle. Grave Business, Skeletons From My Closet, Death Rides A Hearse and more. Deliciously macabre tales of murder with a twist, written by uncelebrated American pulp authors from the 40s and 50s. The first Hitchcock film I remember seeing was North by Northwest, in 16 mm, on a Wadala terrace. Some kind ‘building uncle’ had organised the projector and print. The film dealt with an innocent man on the run. I couldn’t explain what it was that made it such a fantastic viewing experience.

Much before I drank my first beer, I had tasted Hitchcock’s heady cocktail of thrill, tension, black humour, sex and graphic violence. And become an addict. I saw Psycho for the first time at the Film Institute, luckily on the big screen. I got a partial sense of what it must have been like when it was released in 1960. It broke taboos, and how. The shower sequence is still studied in film schools all over. The FTII in the 80s was going through a European cinema phase. Wajda, Bergman, Antonioni, Tarkovsky, were spoken about in awed tones as great filmmakers and poets of the cinema.

But Hitchcock was sort of disparaged. okay, he makes good thrillers. The disdain used to fill me with murderous rage. And then I came across a Steven Spielberg interview where he said, “Any filmmaker who says he is not influenced by Hitchcock is clean out of his mind.” Spielberg’s Jaws (1975) is prime proof of the Hitchcock influence. When the young director found the mechanical shark was not up to expectations, he asked himself how Hitchcock would solve the problem. Hitchcock was adept at creating violence entirely in the viewer’s mind. What you don’t see, scares you so much more.

Hitchcock has influenced filmmakers all over the world including my own favourite Vijay Anand. There is a scene in Kala Baazar which has Dev Anand as the black marketeer, selling tickets at then Bombay’s Metro cinema. The movie playing is North by Northwest. Housefull of course! I often wonder whether Goldie Saab got inspired to write Jewel Thief, (the best Hindi mainstream suspense ever) after watching N by NW. Both films are about a man mistaken for another. This is ‘inspiration’ in the best sense of the word.

In India, even esteemed reviewers confuse a whodunit for suspense. In a career spanning 55 films, the master of suspense made only one whodunit, Murder (1930). He dismissed the genre as a guessing game. Suspense is anticipation, you know everything except what happens next. Suspense is the spying wife stealing a key from her husband’s room and suddenly he emerges from the shower. He comes to her lovingly and wants to kiss her hands. And we know that one of them holds the stolen key. Will she be caught? That’s a scene from Notorious, a spy film without a single scene of violence.

There are few artistes whose names have gone into the language. Hitchcockian, according to the Macmillan dictionary means “very exciting and full of suspense (= the feeling that something bad is about to happen but you do not know what or when).” A serial killer escorts his next victim home and the camera discreetly follows them, until the villain shuts the door on the camera. The camera now pulls back as discreetly and gets back on the street. And waits, and waits, till we hear a distant scream. (FRENZY)

An apartment block where we see a whole lot of people doing their own thing and the camera pans inside the house to a broken still camera, framed photographs of famous events, to eventually reveal the protagonist on a chair, his leg in a cast. And I, the viewer, am instantly plunged into the premise of Rear Window. I watch Hitchcock films over and over again. I know the plot, I know the shots. And yet, there is always something to enjoy, anticipate, discover and learn from them. What I love about Hitchcock is his use of the camera to tell the story. He came from silent cinema and believed in visual storytelling.

Hitchcock abhorred what he called talking heads and even in his silent work, he used less title cards than the others. Hitch loved experimenting. Setting up challenges for himself. What if we do a film in a single shot? If a movie is entirely set in a lifeboat? Or we shoot a play like a play but in 3D? Hitch delighted in pleasing the crowd but he never pandered to them.

In Vertigo, he gives away the crucial plot twist to the viewer much before the climax, because he wants the viewer to invest in the tragic love story. Hitchcock directed the audience as much as he directed the film. Most filmmakers of the time told their stories in third person. The camera is a neutral observer as the film unfolds. Hitchcock shot in first person. We see what characters are seeing. We are in their heads, almost. This Point-of-View technique instantly connected the character to the viewer.

The viewer was a vital part of Hitchcock’s creative process. It is this total involvement and identification with the protagonist that makes every viewer of Psycho shift from being Marion Crane to Norman Bates in the span of a single scene. Psycho is the mother of all slasher films, pardon the pun. As a viewer, I used to delight in spotting Hitchcock’s playful cameos in his films. He died in 1980, and there have been many great films and filmmakers since then. But I see the rotund visage pop up every now and then in the best of films made the world over, scenes that make me want to scream aloud, that’s Hitchcock!

– Sriram Raghavan

You may like

Sriram Raghavan’s Merry Christmas surpasses Andhadhun to hit 8.8 IMDb Rating

Merry Christmas Review: A delightful mystery thriller!

Katrina Kaif: “Working with Sriram Raghavan sir was a dream come true for me”

Agastya Nanda to star in Sriram Raghavan’s Ekkis; shooting commences in January

Sriram Raghavan’s Merry Christmas gets a new release date

Katrina Kaif and Vijay Sethupathi starrer ‘Merry Christmas’ prepones its release by a week